1. Introduction: Why Learn Hanyu Pinyin?

1.1 Importance of Chinese Pinyin

Pinyin is the official romanization system for Mandarin Chinese (also called Putonghua). Developed in the 1950s and officially adopted in 1958, Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet to represent Chinese sounds. For English speakers and other non-native learners, mastering Pinyin is crucial because it helps you:

-

- Learn Chinese pronunciation more effectively.

- Type Chinese characters using a Chinese input method on computers or mobile devices.

- Read transcribed names or places (e.g., “Beijing” instead of the older “Peking”).

- Acquire Mandarin Chinese vocabulary more systematically.

In earlier times, systems like Wade-Giles were common (leading to spellings like “Peking” or “Kungfu”). Today, Hanyu Pinyin is the standard you need to focus on for practical usage in mainland China and most Mandarin-learning environments.

1.2 Who is this Learning Pinyin guide for?

- Total beginners in Mandarin Chinese who want a systematic way to pronounce words.

- Learners who already know some Chinese words but want to correct or refine their Chinese pronunciation.

- Enthusiasts interested in Chinese linguistic aspects, such as Chinese tones and phonetics.

2. What Is Pinyin Made Up Of? (Initials, Finals & Tones)

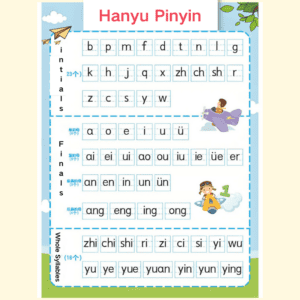

2.1 Initials (Consonant-Like Sounds) and Finals (Vowel-Like Sounds)

In Hanyu Pinyin, a syllable generally consists of an initial (similar to a consonant) and a final (similar to a vowel). For instance, the Chinese character 酒 (jiǔ) has an initial “j” and a final “iu.”

- Common Initials (23 total) include:

b, p, m, f, d, t, n, l, g, k, h, j, q, x, zh, ch, sh, r, z, c, s, y, w - Common Finals (around 33) can be grouped as:

a, o, e, i, u, ü, ai, ei, ao, ou, an, en, ang, eng, ong, ia, ie, iao, iou (or iu), ian, in, iang, ing, iong, ua, uo, uai, uei (or ui), uan, uen (or un), uang, ueng, üe, üan, ün…

Note on “ü”:

Because most English keyboards don’t have the letter “ü,” Chinese input methods typically replace “ü” with “v” or “uu.” For example, “lǜ” (to mean “green” in some contexts) becomes “lv” or “luu” when typing.

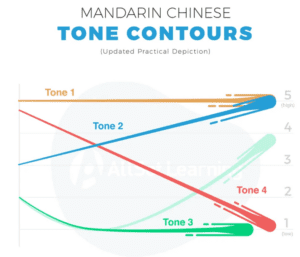

2.2 The Four Tones and the Neutral Tone

Mandarin Chinese has five tonal categories (four main tones + one neutral tone):

- First Tone (ˉ): high and level (e.g., mā).

- Second Tone (ˊ): rising (e.g., má).

- Third Tone (ˇ): low dip, then rising (e.g., mǎ).

- Fourth Tone (ˋ): falling sharply (e.g., mà).

- Neutral Tone: light and unstressed (written with no tone mark, e.g., ma).

Each Chinese syllable carries a tone, and changing the tone can alter the meaning completely.

2.3 Special Syllables: Zhi, Chi, Shi, Ri, Zi, Ci, Si

Some Pinyin spellings look like an “initial + i” structure but actually function as one combined sound:

- Zhi (知): resembles “jer” in “jerk” (with a retroflex twist).

- Chi (吃): similar to “chur” in “church.”

- Shi (是): akin to “shur” in “shirt.”

- Ri (日): has an “rrrr” retroflex sound, with the tongue curled back.

- Zi (子): close to the “ds” in “suds.”

- Ci (此): akin to the “ts” in “cats.”

- Si (四): somewhat like “ss” in “hiss,” but with a subtle “-r” tail in Mandarin.

Instead of reading them as separate letters (z + h + i, etc.), treat them as unique syllables. This approach helps avoid common pronunciation mistakes.

3. Real Pinyin Pronunciation Challenges and Correction Tips

3.1 Distinguishing Similar Sounds: j, q, x vs. zh, ch, sh

English speakers often struggle to differentiate between “j, q, x” (flat tongue) and “zh, ch, sh” (retroflex tongue). For example, “xiǎo” (小) is often mispronounced as “shǎo” (少).

How to practice:

- Use a mirror to observe tongue placement: for “j, q, x,” the tongue should stay close to the lower teeth; for “zh, ch, sh,” the tongue curls back.

- Listen to native speakers and mimic their pronunciation, focusing on subtle differences.

- Practice pairs of words with contrasting sounds, like “xī” (西, west) vs. “shī” (师, teacher).

3.2 Mastering Tone Sandhi and Natural Tone Changes

One of the biggest challenges in learning Mandarin is understanding and applying tone sandhi, especially the changes in the third tone. For example, in “nǐhǎo,” the first word’s tone changes to the second tone, becoming “níhǎo.”

How to practice:

- Break sentences into smaller chunks and focus on tone changes word by word.

- Use apps or recordings with slowed-down pronunciations to observe and mimic tone sandhi.

- Practice common phrases like “hěn hǎo” (很好, very good), where tone changes frequently occur.

3.3 Distinguishing “u” from “ü”

- u: Similar to the “oo” in “room.”

- ü: Lips start in an “ee” position, then round slightly, like “lyu.”

When typing, “ü” is replaced by “v” or “uu,” so “lǜ” becomes “lv” or “luu.”

3.4 Pronunciation of Retroflex and Nasal Finals

Mandarin includes retroflex finals like “-er” (儿) and nasal finals like “-ang” (昂) and “-eng” (恩), which may not exist in English.

How to practice:

- Retroflex finals: Practice words like “ér” (儿, child) by exaggerating the tongue curling motion until it feels natural.

- Nasal finals: Hold the ending sound slightly longer to distinguish between “-ang” (e.g., zhāng, 张) and “-eng” (e.g., zhēng, 睁).

- Use minimal pair drills, such as comparing “làng” (浪, wave) and “lèng” (愣, stunned).

3.5 Overcoming Listening Challenges

Even if you master pronunciation, recognizing tones and subtle differences in spoken Mandarin is another hurdle. Words with the same initials and finals but different tones, like “mā” (妈, mom) and “mǎ” (马, horse), can cause confusion.

How to practice:

- Focus on tone recognition drills using flashcards or audio apps.

- Listen to slow, clear recordings of native speakers before gradually transitioning to faster-paced speech.

- Practice dictation exercises: listen to sentences and write down the Pinyin with tone marks.

4. Using Pinyin for Chinese Input

4.1 Overview of Chinese Input Methods

Popular tools include:

- Microsoft Pinyin,

- Sogou Pinyin(most popular in China),

- Google Pinyin.

You type initials and finals, and the software suggests corresponding characters:

- Typing “zhongguo” → “中国” (China)

- Typing “nihao” → “你好” (Hello)

4.2 Handling Special Vowels or Characters

- ü becomes v or uu in many systems (e.g., lǜ → lv).

- If your textbook says “jüé,” input methods often just require “jue.”

4.3 Word Association and Learning

Most input methods offer predictive text or auto-complete features. As you type frequently used words, you build a mental map of Chinese vocabulary. For example, after learning “打开 (dǎkāi, to open),” you can also discover related terms like “打字 (dǎzì, to type)” or “打车 (dǎchē, to take a taxi).”

4.4 Going Beyond Pinyin Input

While Pinyin helps you write characters, remember that recognizing and understanding the characters themselves is vital for literacy in Chinese. Pinyin is an essential bridge, but the ultimate goal is reading and writing Chinese characters.

5. Mindset and Study Methods of Learning Hanyu Pinyin

5.1 Balancing “Rules” and “Imitation”

- Rules Approach: learn the technicalities—initials, finals, tone sandhi—early on.

- Imitation Approach: rely on repeated exposure to authentic Chinese (listening, speaking, recording).

For non-native speakers, initially grasping these rules speeds up learning. Then, reinforce by imitating native speakers in real situations.

5.2 Don’t Obsess Over Tone Marks

Native speakers rarely think about “Is it second tone or third tone?” when they speak. They do it intuitively, much as English speakers naturally produce correct vowel sounds without reciting phonics rules. Use tone marks for reference, but long-term success hinges on consistent listening and practice.

5.3 The Third Tone in Daily Speech

- “nǐhǎo” often sounds like “níhǎo.”

- Don’t be alarmed if you hear slight variations. Different regions and speakers handle tone changes slightly differently.

5.4 Steady Progress and Consistent Practice

- Pinyin is the foundation, but building large vocabulary and reading ability requires patience and regular exposure to Chinese.

- Engage with native speakers, watch Chinese videos, or try guided practice sessions.

6. A Brief Look at Pinyin Culture and History

6.1 The Creation and Promotion of Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin was introduced in the 1950s to unify pronunciation standards in mainland China and facilitate literacy. Children in Chinese schools learn Pinyin first, then transition to characters.

6.2 Other Romanization Systems

- Wade-Giles: popular in the early 20th century; hence “Peking” (Beijing) or “Tsingtao” (Qingdao).

- Bopomofo (Zhuyin Fuhao): used mainly in Taiwan, employing special symbols like ㄅ, ㄆ, ㄇ, ㄈ.

6.3 Chinese Pinyin Databases and Extensions

Modern Pinyin input methods often include thousands of Chinese characters and phrases. If a particular word is missing, you can usually add it manually or update the dictionary.

7. FAQs: Mastering Pinyin Learning, Pronunciation, and Tones

- What are the most common mistakes beginners make in Pinyin pronunciation?

Beginners often confuse the retroflex sounds like “zh, ch, sh” with their flat-tongue counterparts “j, q, x.” Another common issue is distinguishing between “u” and “ü.” Use a mirror to check your tongue position and practice listening to native speakers to refine your pronunciation. - How can I master Chinese tones more effectively?

Mastering tones requires consistent practice. Start by learning the basic four tones and the neutral tone. Then, practice with common phrases like “nǐhǎo” (hello), focusing on natural tone changes like tone sandhi. Using audio shadowing techniques can help solidify your tonal accuracy. - Are there tips for using Pinyin input methods efficiently?

Yes! Familiarize yourself with how to type “ü” using “v” or “uu” (e.g., typing “lǜ” as “lv”). Leverage predictive text features in tools like Microsoft Pinyin or Sogou Pinyin to discover related terms and build your vocabulary. - When should I transition from Pinyin to learning Chinese characters?

Once you’re comfortable with Pinyin basics, start learning common Chinese characters. Pinyin is a bridge, but true literacy in Mandarin depends on character recognition and writing. - How do I practice Pinyin pronunciation daily?

Incorporate techniques like shadowing (repeating after native speakers) and recording yourself reading Pinyin phrases. Apps or resources with native audio examples are excellent for improving both pronunciation and tone recognition. - How do I pronounce tricky syllables like “zhi,” “chi,” and “shi” correctly?

These sounds require a retroflex tongue position—curl your tongue slightly back while keeping steady airflow. Practice with words like “zhī” (知), “chī” (吃), and “shī” (是), and listen to recordings to fine-tune your articulation. - Is it normal to struggle with tones at the beginning?

Absolutely! Tones can be challenging for beginners, but with regular listening and repetition, you’ll gradually improve. Focus on clarity and natural flow rather than perfection in the early stages. - Do I need to master tone sandhi rules for fluent Mandarin?

Yes, understanding tone sandhi (tone changes in natural speech) is essential. For example, in “nǐhǎo,” the first third tone changes to a second tone, making it “níhǎo.” These rules will become second nature with practice. - How important is Pinyin for learning Mandarin pronunciation?

Pinyin is crucial for mastering Mandarin pronunciation. It helps English speakers understand how to pronounce Chinese sounds accurately, making it an essential tool for building vocabulary and speaking fluently. - What are the best resources for improving Pinyin skills?

Online tools like Pinyin practice apps, audio dictionaries, and video tutorials from native speakers are excellent resources. For input methods, Sogou Pinyin and Google Pinyin provide predictive text and tone practice features.

Related Useful Articles

Exploring the “Chinese Alphabet”: Discovering the Unique World of Hanzi

Learn Chinese in 2025: Unlock Global Success and Career Opportunities